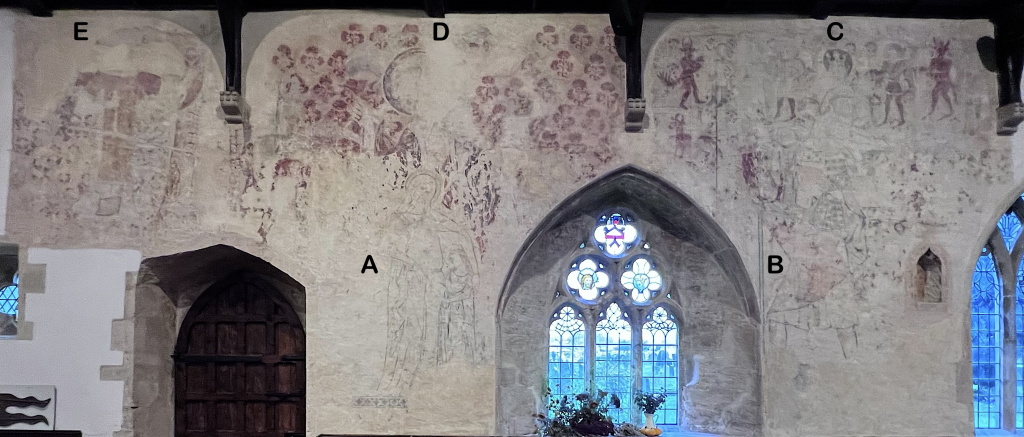

At first sight, the paintings in the north aisle are a confusing muddle. To make sense of them, it helps to understand that they comprise two layered sets of paintings, one layer dating from the 14th century (paintings A and B) and the other from the 15th century (paintings C, D and E).

The north aisle was built as a Lady Chapel before 1319 by Dame Margery de Crioll; her will (dated 1319, at Lincoln) leaves bequests to the Priests “in the chapel of Our Lady which I have built in Corby Church”. The lower paintings (A and B) are from this period:

- A St Anne teaching her daughter, the Virgin Mary, to read

- B St Christopher carrying the Christ Child

About 1400 or soon after, the aisle was lengthened, forming a chapel on the north of the chancel where the Lady Altar was transferred. At the same time, the aisle wall was raised. This meant that the existing paintings (A and B) were damaged. The medieval decorators did not attempt to restore them, but covered them with a thin wash of lime-putty, and repainted the whole wall (paintings C, D and E):

- C The Seven Deadly Sins and a Warning to Swearers (painted over St Christopher, painting B)

- D St Christopher (painted over painting A as a replacement for the St Christopher in painting B)

- E St Michael and the Virgin of Mercy

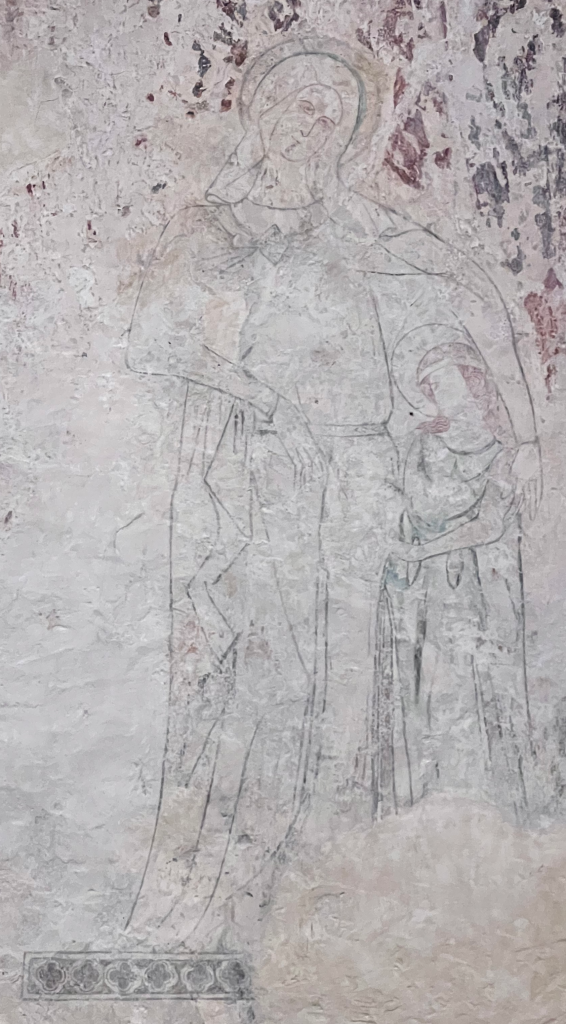

A: St Anne teaching the Virgin Mary to read

One of the oldest wallpaintings in Corby Glen Church is an above life-size representation of St Anne teaching her daughter, the Virgin Mary, to read. It dates from the early 14th century, and is one of the most complete and accessible paintings. It is to the right of the north door.

Clive Rouse described the painting as follows:

The work is almost in outline with faint shading of the draperies in blue-black, and a sparing but effective use of colour.

The features and hair are drawn in red and the saint’s nimbus [halo] and morse and the jewels on the girdle are in green, a rare and expensive colour which is also used for the Virgin’s robe.

The book that the Virgin was holding has perished. The two figures, delicately and gracefully posed, stand on a dado of quatrefoils.

The Church of St John the Evangelist, Corby, Lincolnshire, by E Clive Rouse (1941)

B: St Christopher carrying the Christ Child

This 14th century painting of St Christopher carrying the Christ Child lies partly beneath a later painting, hence the somewhat confusing appearance. Clive Rouse’s rendition of the painting may help with interpreting what is seen.

To quote Rouse’s description:

The rebuilding of the upper part of the wall has destroyed the heads of both the Saint and of the Christ, and the base was damaged by the insertion of a mural tablet (now moved elsewhere) and the failure of the plaster due to damp. However, the painting exhibits several remarkable features.

The Saint is clad in a pink cloak lined with green, the double drapery folds falling from his left arm. He grasps his staff of green outlined in black in his right hand, leaning on it, while the knees are bent in the effort of forging across the stream, a tiny fragment only of which in grey-green with black lines is preserved at the base. The Saint’s figure is immense, being about nine feet high.

The Child is held on the Saint’s left shoulder. He has bare feet and is clad in a most remarkable peacock robe with elaborate neck- and hem-edgings and belt. His right hand is raised in blessing and his left grasps the lower part of the orb, in black outline with wavy green and yellow bands.

The pose of the whole composition is graphic and vigorous.

The Church of St John the Evangelist, Corby, Lincolnshire, by E Clive Rouse (1941)

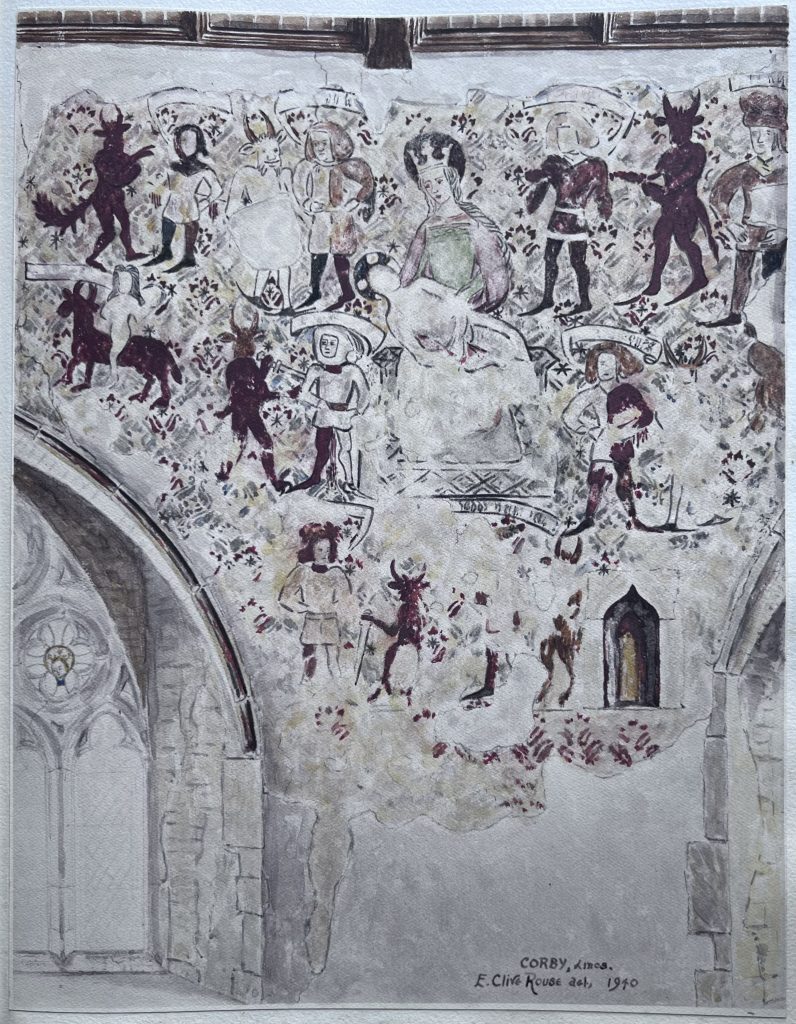

C: The Seven Deadly Sins, and a Warning to Swearers

This 15th century wallpainting was painted over the 14th century image of St Christopher after the north aisle roof had been raised. It is an unusual combination of two subjects: the Seven Deadly Sins, and a warning to swearers by the incorporation of La Pieta, an image of Mary holding the body of Jesus after his death on the cross.

Once again, Clive Rouse’s depiction and description of the scene might help with its interpretation.

In the centre is Our Lady of Pity (La Pieta) – the Virgin, enthroned, holding the body of the dead Christ; and surrounding this are numerous groups of figures of young men in the height of the exaggerated fashions of the early 15th century, each accompanied by a devil.

The whole is set on an elaborate brocade-pattern background in which the artist has used the same stencil as in the Weighing of Souls [painting E], but has placed the lower parts differently so as to vary the design, moreover painting these in blue-grey and adding a black star in the apex.

The work is fragmentary toward the bottom, where it was merely carried over the older painting on whitewash, and was, moreover, mutilated by a monument, now removed.

The subject resembles very closely the arrangement of a stained glass window, now destroyed but fortunately recorded, at Heydon, Norfolk, and a wall painting, also perished, at Walsham-le-Willows, Suffolk.

It will be noted that above each figure is a scroll issuing from the mouth. The inscriptions on these are illegible except for a few letters: one ends “…ones” and probably read “By Goddes Bones”.

But in the other examples each contained an oath on some part of Our Lord’s body, and the scroll beneath the Virgin and Christ contained a lament of the Mother over her Son – this also appears at Corby. It was inscribed “the cursed sweareres, albeit his limbes be rent assundered”. At Broughton, Bucks, the same subject is portrayed; in this case Our Lord’s body is mutilated and the youths hold portions of it.

The vice of swearing in this way was very prevalent in the late 14th and early 15th century, and is alluded to by Langland, Chaucer and other contemporary writers. It is not possible to see whether Our Lord’s body is mutilated in this case; but the teaching of the painting is clear – it is a warning to swearers and blasphemers that by so doing they re-crucify Christ and add to Our Lady’s woes.

In this case, the matter goes further: for the introduction of the devils does not occur in any of the other three similar examples in England. It will be seen that there are seven of them: and in two of the scenes two figures occur. We thus have combined with the Warning to Swearers (itself an unusual and interesting subject) a most unusual treatment of the Seven Deadly Sins.

It is not possible to identify them all. The one on the top right hand, where the devil is between two youths, is probably Anger (Ira), the devil inciting them to fight; while the first on the left in the middle row is Lust or Lechery (Luxuria), the nude female temptress riding off on a devil horse.

The swords piercing the side and feet of two youths are references to the wounds in the side and feet of Christ. Note how one devil has a youth by the toe of one of his absurdly long pointed shoes. Note also the extravagant fashions of parti-coloured doublets and hose, three styles of fancy hood, hairdressing, long sleeves and so on – all points mentioned in Chaucer’s discourse on the Seven Deadly Sins in the Parson’s Tale.

The little image-niche of the early 14th century was filled up and plastered over at this period; now cleared, it shows its original outline in colour bands, and on the back and sides.

The Church of St John the Evangelist, Corby, Lincolnshire, by E Clive Rouse (1941)

D: St Christopher (15th century)

As noted above, when the north aisle roof was raised, the original painting of St Christopher was covered over by a new painting showing the Seven Deadly Sins. However, because of the popularity of St Christopher as the patron saint of travellers, it was necessary to include a new depiction somewhere in the church, and preferably visible from the main door as people entered the building. So it was painted over the earlier image of St Anne teaching St Mary.

To quote Rouse again:

The lower part was very fragmentary and was removed to expose the exquisite earlier subject [painting A]. The top, however, on the newer plaster is fairly complete. An intermediate roof-bracket (removed) unhappily came in the centre of the Saint’s face.

The Saint is of even more colossal proportions than the earlier painting [painting B]. The large and elaborate halo is clear, also the hand grasping the top of the staff, shown as flowering in accordance with the legend. The drapery folds of the cloak remain, but the figure of the Child has perished.

At the extreme left the Hermit’s cell is represented, with a little spire and porch.

Once again there is an elaborate background, this time consisting of a conventional branching tree or flower, and also painted with a stencil.

The Church of St John the Evangelist, Corby, Lincolnshire, by E Clive Rouse (1941)

E: St Michael and the Virgin of Mercy

Although medieval images of St Michael weighing souls in a balance are more common, the inclusion of the Cistercian motif Vierge de la Misericorde showing St Mary sheltering souls under her cloak makes this painting a unique survival in the UK.

This image is contemporary with paintings C and D, being produced around 1400 or soon after, to judge by the costume.

Clive Rouse described it thus:

The composition, though damaged by plaster failures and the insertion of later roof brackets, is striking. St Michael, in apparelled and fringed vestments, stands in the centre (the face and upper part of the wings are destroyed) holding a large balance. A small devil sits astride the west end endeavouring to push the scale down, and so gain the soul faintly visible in the other pan. But the Virgin, a graceful figure as tall as St Michael, but mutilated by the roof bracket, places the beads of her rosary on the other end of the beam, thus tilting the scale in favour of the soul.

The interesting and unique point about the composition is that Our Lady is seen at the same time protecting souls, grouped in pairs, under the folds of her cloak. This is a common feature on the Continent, but is the only surviving example in this country.

At the foot of St Michael kneels the small figure of a priest being presented to the Virgin and having above him a scroll inscribed in English. It probably represents the donor of the painting, most likely the Vicar of the time. The whole composition has an elaborate brocade-pattern background in deep red, painted with a stencil.

The Church of St John the Evangelist, Corby, Lincolnshire, by E Clive Rouse (1941)